LITERATURE ▶

IN SEARCH OF THE SINGAPORE PLAY. A FEW THOUGHTS ON THE SLOW BIRTH OF SINGAPOREAN DRAMA

MARC GOLDBERG

A transcription of Marc Goldberg’s contribution to the colloquium The emergence and vicissitudes of an art scene, musée du quai Branly, Paris, 4 June 2015.

Let me first stress that these thoughts are grounded on an essay on the role of monodrama in the history of Singapore theatre which I wrote for a CIRRAS collective work1, as well as on my research regarding Two Singapore Monodramas, a project I designed for the Singapore Festival in France that consisted in the presentation and dramatised readings of the two groundbreaking Singapore plays which put an end to the quest of the Singapore Play in so far as they are widely considered to be the coming of age of Singapore Drama2.

A transcription of Marc Goldberg’s contribution to the colloquium The emergence and vicissitudes of an art scene, musée du quai Branly, Paris, 4 June 2015.

Let me first stress that these thoughts are grounded on an essay on the role of monodrama in the history of Singapore theatre which I wrote for a CIRRAS collective work1, as well as on my research regarding Two Singapore Monodramas, a project I designed for the Singapore Festival in France that consisted in the presentation and dramatised readings of the two groundbreaking Singapore plays which put an end to the quest of the Singapore Play in so far as they are widely considered to be the coming of age of Singapore Drama2.

These two famous plays are Emily of Emerald Hill by Stella Kon and The Coffin is Too Big for the Hole by Kuo Pao Kun.

I will briefly talk about them later, but let me immediately stress that they were both staged in 1985. That is, Singaporeans actually had to wait 20 years after independence to reckon that their national theatre was unquestionably born. My objective is to share a few thoughts about this slow birth, and more specifically about a few impediments that prevented Singapore Drama to develop faster.

Before the Quest

The Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall completed in 1862.

The Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall completed in 1862.

As a matter of fact, one could have expected Singapore Drama to grow quickly, because there was an old, rich and diverse tradition of performing arts in Singapore before theatre practitioners actually launched their quest for the Singapore Play.

Singapore's modern History begins around 1818 and we have evidence of English drama performances taking place in the new British settlement as soon as 1833. Moreover, the communities that started to gather in the island were all bringing their own performing arts. That is to say that, by the beginning of the 20th century, one could attend many different kinds of traditional Asian performing arts, be they Malay, Chinese, or Indian, as well as modern theatre, Western of course, but also Chinese since there are records of huaju (话剧, the Chinese modern Western-style theatre) performances in Singapore as soon as 1913.

Very few countries may claim such diversity, in style as well as in origin, regarding their performing arts scene. Here is, for instance, a selection of English speaking performances one could attend in Singapore in 1964, one year before independence, which includes entertainment (from Arsenic and Old Lace to The Madwoman of Chaillot) as well as classics (Shakespeare of course) or modern playwrights such as Thornton Wilder:

The (unofficial) theatre guide in 1964

A sampling of what a theatre-goer could watch in 1964, collected by Centre 42 for The Vault project (centre42.sg/va-1-unofficial-1964-theatre-guide)

- Akin to Love by Peggy Simmons

- Salad Days by Julian Slade & Dorothy Reynolds

- I’m Bewitched by Friar T.J. Sheridan

- Twelfth Night by William Shakespeare

- Trial and Error by Kenneth Horne

- Distinguished Gathering by James Parish

- A White Rose at Midnight by Lim Chor Pee

- The Matchmaker by Thornton Wilder

- The Brides of March by John Chapman

- Arsenic and Old Lace by Joseph Kesselring

- Moon on a Rainbow Shawl by Errol John

- Naked Island by Russell Braddon

- Outward Bound by Sutton Vane

- Chicken Soup With Barley by Arnold Wesker

- The Madwoman of Chaillot by Jean Giraudoux

- The Tunnel of Love by De Vries and Joseph Fields

- Cinderella [pantomime]

So how come critics and practitioners usually consider that nobody was able to craft a genuine, authentic, totally convincing Singapore play before 1985? There are many elements at stake, and a meaningful way to unravel a few impediments is to examine the three main components of the Singapore scene (that is to say traditional performing arts, modern Chinese drama, and English speaking drama), in order to understand why they were not immediately ripe enough to engender the Singapore Play.

The reason why traditional performing arts did not father the Singapore Play is quite obvious, but it tells a lots about the obstacles theatre practitioners would have to overcome in order to devise a national play. Traditional performing arts, as much as cooking or rituals, are bound to a community and do not naturally seek to address anybody beyond that community. Now, if a nation is built (be it through a gradual historical process, some violent political events, a mythological narrative, or any blend of these elements) on a specific community (real or fantasized), this community's cultural practices, including performing arts, may evolve into national arts; but, precisely, there is no such community in Singapore when the island turns into an independent State. Geographically and archaeologically, Singapore is linked to Malaysia, but since the middle of the 19th century it is demographically Chinese even though, culturally, it might not be that meaningful since so many Chinese minorities, with different languages, cultures (including performing arts) and heritage are labelled “Chinese”. Then, historically, Singapore was part of the British Empire for one century and a half, and the beginnings of its modern development took place within this colonial frame. Also, what about the large Indian community, with its various performing arts traditions?

Moreover, not only could no community naturally impose its cultural leadership on Singapore, but it was a deliberate political, almost ontological choice to prevent any community from imposing its language, its culture, its values to the others. From the beginning, Singapore opted to be a multilingual and multicultural nation, which means that traditional performing arts were bound to remain confined to the limits of their community. Then, in Singapore as in many developed countries, folklorisation appears to be the unavoidable fate of traditional arts: they loose their meaning and creativity as modern life uproots them from their social and cultural original context.

Failure of the Wayang Peranakan

Rusiah, 1967.

Rusiah, 1967.

To my knowledge, the only exception could have been the wayang peranakan, which was a very interesting form of local hybridisation. It derives from the bengsawan, a Malay form of drama which itself seems to stem from an Indian tradition. The Malay bengsawan was then adopted and adapted by the Peranakans, the descendants of Chinese traders who settled in South-East Asia centuries ago, married local women and developed an idiosyncratic culture before playing an instrumental part in the development of the Malacca Strait colonies. Traders and craftsmen, they were naturally involved in the reshaping of the region, and the British used them as middle-men for their imperial agenda. Their local elite status is probably a reason why, at the beginning of the 20th century, they developed the wayang peranakan, an original performing arts form that could have challenged both traditional and modern theatre as a local new practice, stylistically quite traditional, but infused with contemporary characters and issues.

However, by the beginning of the 1960s, the wayang peranakan had almost disappeared, preventing it from becoming the mould of the Singapore Play (even though it clearly influenced Stella Kon's Emily of Emerald Hill). Various elements contribute to explain this failure. The main one is probably historical. As much as Peranakans had benefited from the development of the Straits Colonies under British rule, they were persecuted during Japanese occupation (1942-1945) and did not manage to re-establish their position during the decolonisation process: in this context, wayang peranakan was not able to reinvent itself and unfortunately soon turned into just another folkloric performing arts form.

A State without a Nation

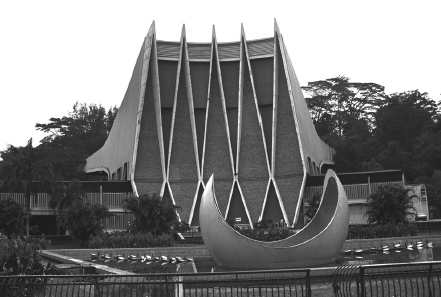

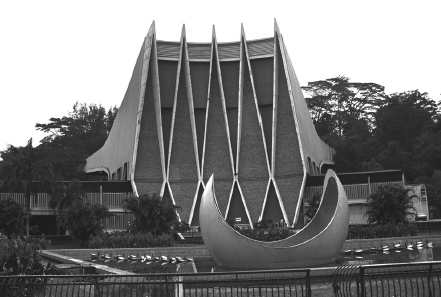

The National Theatre opened in 1963, demolished in 1984.

The National Theatre opened in 1963, demolished in 1984.

Traditional performing arts, far from leading the way towards the Singapore Play, actually underline a major impediment that theatre practitioners would have to overcome after independence before crafting Singapore Drama (an obvious but essential impediment): when Singapore is expelled from Malaysia in 1965, there is no Singapore identity, no Singapore culture, no Singapore nation – just a State to handle a mere collection of communities which had decided, for various reasons, to settle on this tiny island, predominantly less than a century ago.

Now Chinese modern drama (huaju) could have played a defining role in the invention of Singapore drama, if only because this non-traditional performing art could potentially gather all Singapore Chinese people, that is to say about 75% of the population. However, it did not.

According to me, the prime reason why it did not, is just that it did not want to. From the beginning, huaju had been involved in politics, in mainland China as well as in Singapore. During the 1960s, when the quest for the Singapore Play begins, Singapore Chinese western-style drama is still following mainland China theatre, that is to say a proletarian internationalist agenda, far from any local national concerns despite Singapore joining Malaysia in 1963 then becoming independent in 1965.

Performing International Plays

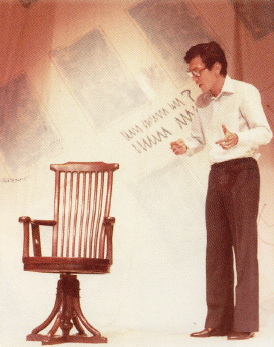

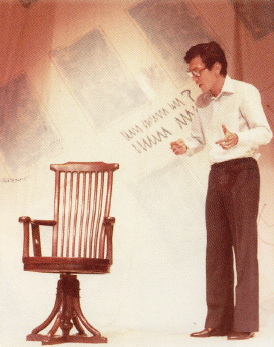

Lorraine Hansberry, A Raisin in the Sun, translated and staged by Kuo Pao Kun, 1967.

Lorraine Hansberry, A Raisin in the Sun, translated and staged by Kuo Pao Kun, 1967.

A dance created by the Kuo Pao Kun company after experiencing life in a pineapple plantation, 1972.

A dance created by the Kuo Pao Kun company after experiencing life in a pineapple plantation, 1972.

Kuo Pao Kun (1939-2002), who had launched the first professional theatre school in Singapore in 1965, and who was already the leading figure of Chinese drama, is emblematic in this regard. During independence years (before spending the second half of the 1970s in jail as a political prisoner), he would mainly stage two types of plays:

- Adaptations of plays about social and political issues, such as The Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry (an American play about racial segregation in Chicago performed on Broadway in 1959), which were meant to raise social consciousness and denounce oppression.

- Shows directly inspired by communist Red theatre as it was then developed in mainland China: for example, Kuo Pao Kun and his company would share the life of peasants and fishermen, devising the performance with and for those workers.

Nation building, national drama, were not part of this internationalist political theatre, which vanished after the 1970s, because many artists had been jailed, but also because the Cultural Revolution ideals were eventually rejected both in mainland China and South East Asia. Let us then just underline that Singapore geopolitical situation in the 1960s and 1970s was clearly another impediment to the development of Singapore drama, both because communism was favouring internationalist and ideologically driven arts forms rather than local and innovative styles, and because internal political struggles and repression definitely reduced creativity on the Singapore scene.

What about the third component of the Singapore scene then, English speaking drama? It was definitely the English drama practitioners who launched the quest for the Singapore play, and one might even say that the official starting point was an article by Lim Chor Pee published in 1964. The title of the article was Is Drama Non-existent in Singapore? and his answer was blunt: Singapore Drama had yet to be invented.

Longing for Singapore Drama

"One of the factors that has retarded the establishment of an English speaking theatre in this country is that almost every play that is produced here is one superficial piece of Western drawing room drama. After a while, it gets very boring because theatre is essentially a reflection of truth and not the false and unattainable dreams of the Western middle-class.

Therefore, whatever Western play that is staged is either lost or failed to be appreciated, for those plays reflected a glory that is past or imagined. I refer particularly to the Victorian and Edwardian drawing room drama, which, so we are told, was how the Englishman lived. Did they? We are not so sure. To put it simply, they just do not concern us."

Lim Chor Pee, Is Drama non-existant in Singapore?, Tumasek, 1964

Lim Chor Pee's point is quite straightforward: English speaking drama is still fundamentally colonial in early independent Singapore. It does not deal with local issues, does not present local characters, does not stage local stories. Its scripts, its aesthetics, its role models all come from the former colonial power: Great Britain.

This is quite common in any post-colonial culture, but the issue was locally compounded by the specificities we mentioned earlier: it is obviously much harder to get loose from the former imperial subjugation when no national nor indigenous alternative paradigm is yet available.

So what should theatre practitioners do, according to Lim Chor Pee? They should try to write their own plays: “There can be no proper theatre unless there are playwrights” is a defining statement from his seminal essay.

As a matter of fact, he had already tried, and he would try again, as well as another main figure of independence days Singapore literature: Goh Poh Seng.

Crafting the Singapore Play: Independence Days

"There can be no proper theatre unless there are playwrights."

Lim Chor Pee, Is Drama non-existent in Singapore?, Tumasek, 1964

Lim Chor Pee (1936-2006), author of Mimi Fan (1962) and A White Rose at Midnight (1964).

Lim Chor Pee (1936-2006), author of Mimi Fan (1962) and A White Rose at Midnight (1964).

Goh Poh Seng (1936-2010), author of The Moon is Less Bright (1964), When Smiles are Done (1965), The Elder Brother (1966).

Goh Poh Seng (1936-2010), author of The Moon is Less Bright (1964), When Smiles are Done (1965), The Elder Brother (1966).

Lim Chor Pee, a Cambridge trained lawyer and theatre enthusiast, was a major figure of Singapore English drama during the first half of the 1960s, both as a theoretician, a company director and a playwright. Mimi Fan, his first play, is considered the first attempt to craft an English speaking Singapore play. Staged in 1962, Mimi Fan is definitely a fine play, but Lim Chor Pee is right to suggest that, in 1964, Singapore drama is still non-existent despite his own attempt.

Why? To put it bluntly: Mimi Fan is not a real Singapore play, but rather a Western play that takes place in Singapore. For instance, the characters are supposedly Singaporeans, but they basically talk like Englishmen (as a matter of fact, the few localisms Lim Chor Pee adds even make it worse). Of course, they are indubitably local people: Chinese, Indian – just one Briton; but, precisely, they are obviously meant to mimic Singapore society, and they generally talk about Singapore society rather than experience and share Singapore stories.

In 1964, he would write and produce another play: A White Rose at Midnight, where we also follow a group of “typical” Chinese and Indian Singaporeans, who talk about love, education, Asian and Western values… Again, it is more a play about Singapore, an attempt to describe Singapore, than a genuine Singapore play. Goh Poh Seng, a Dublin trained physician, wrote three plays during the 1960s (from 1964 to 1966), then also turned away from drama. He went on writing though, poetry and novels, in particular If We Dream Too Long (1972) which is often considered as the first Singapore novel. However, regarding his plays, one could say that they are crippled by the very same issues Lim Chor Pee did not manage to overcome. For example, his first play, The Moon Is Too Bright (1964, which takes place amongst peasants during World War 2, begins with a long naturalistic description of the set and the characters, but here are the first lines of the two poor farmers:

Goh Poh Seng, The Moon is Less Bright, 1964

Kim Hong

Well, no sign of them [the Japanese] yet. It's just as quiet as yesterday morning.

Poh Suan

You wouldn't hear anything, until it happens, until they arrive at your doorstep.

Kim Hong

I suppose you're right, we won't hear them until they descend on our very door-step. Yes, this quietness, this familiarity is deceptive.

In these lines, there is an obvious discrepancy between what the characters are supposed to be, and the way they talk. As a consequence, similarly to Lim Chor Pee's plays, characters tend to look like puppets which are devised to express the author's own thoughts, or prove his views. They lack flesh, dimensionality.

Now, in his last two plays, Goh Poh Seng tried to tackle the issue of language. His characters definitely do not speak British English anymore, and that is a huge step toward crafting a real Singapore play. Nonetheless, one must admit that the way Goh Poh Seng tries to create a Singaporean voice for his characters is quite clumsy, maybe because, instead of finding a proper personal voice for them, he literally stuffs their lines with localisms. As a result, to me and others, even though they do not speak British English, they end up sounding as fake, as distant from “real” people than any previous English speaking Singaporeanish character.

Hence, to sum up the obstacles this first generation of Singaporean playwrights did not manage to master, I would say there were three main impediments, all linked to post-colonialism:

- They wished to write a Singapore play, but their idea of drama was still British: they did not craft (they might even not have sought to craft) a new way, a Singaporean way, to build a local drama, to stage a homegrown story.

- They tried but did not manage to find a voice for their Singaporean characters, to devise a specific theatre language that would allow their characters to sound like proper characters, not mere puppets.

- They failed to tell us Singapore stories: their stories just took place in Singapore, just talked about Singapore.

Stella Kon and Kuo Pao Kun would eventually find solutions to solve these problems some 20 years later, but even though Max LeBlond (a prominent Singapore theatre scholar and stage director) could still state in 1981 that “a truly Singaporean theatre, by Singaporeans, about Singaporeans and for Singaporeans does not exist yet”, things had moved forward since the 1960s with a second wave of English speaking theatre practitioners.

Crafting the Singapore Play: The Second Wave

"A truly Singaporean theatre by Singaporeans, about Singaporeans,

for Singaporeans does not yet exist."

Max Le Blond, 1981

Robert Yeo (1940-), author of Are You There, Singapore? (1974) and One Year Back Home (1980).

Robert Yeo (1940-), author of Are You There, Singapore? (1974) and One Year Back Home (1980).

Max Le Blond (1950-), author of Nurse Angamuthu’s Romance, adapted from Peter Nichols’s National Health (1981) and Samseng and the Chettiar’s Daughter, adapted from John Gay’s Beggar's Opera (1982).

Max Le Blond (1950-), author of Nurse Angamuthu’s Romance, adapted from Peter Nichols’s National Health (1981) and Samseng and the Chettiar’s Daughter, adapted from John Gay’s Beggar's Opera (1982).

First of all, Robert Yeo had started to write a trilogy that he would finish in the 1990s, The Singapore Trilogy, and that, in a way, relaunched the quest for the Singapore Play. The first part, Are you there Singapore? (1974), deals with love, sex, mixed race couples, East and West, as Lim Chor Pee had done in Mimi Fan or Goh Poh Seng in The Moon is Less Bright. However, the action is set in London and, paradoxically, this shift has many virtues. For instance, the Singaporean students characters use a few localisms when they talk together, but they are not supposed to be in Singapore and they often talk to foreigners, so they are entitled to speak British English. As a consequence, for the first time, there is nothing weird about the way these Singaporean characters talk. Also, since the action is not supposed to take place in Singapore, Are you there Singapore? does not look like an English play which happens to take place in Singapore… As a consequence, the lack of genuine Singaporean theatricality is not as blatant. This detour by England was clearly a step forward for Singapore drama: consciously or not, Robert Yeo did not attempt to write the ultimate Singapore Play, which would take place in Singapore, sound Singaporean and tell a local story involving local characters, but he definitely managed to get more Singaporean-ness on stage because the Singapore audience could actually connect with his characters.

Bringing some genuine Singaporean-ness on stage is also what Max LeBlond has in mind in the early 1980s when he adapts, or rather re-writes foreign plays so that they take place in Singapore, so that the characters look and talk like Singaporeans. As a matter of fact, beyond the script, Max LeBlond decided to deal with acting. Singapore playwrights tended to be influenced by British playwrights – Singapore actors tended to be mesmerized by British actors. LeBlond used his tailor-made scripts to convince his casts (as well as the local audience) that they could, and should, talk and behave on stage as Singaporeans. Of course, this was instrumental in the development of a genuine Singapore scene.

In a way, the only element still lacking was local theatricality, something that would immediately differentiate the Singapore Play to come from any British play so that not only the character, not only his voice, not only the story, but the dramaturgy, would be Singaporean. That is precisely what Emily of Emerald Hill and The Coffin is Too Big for the Hole achieved.

The Coming of Age of Singapore Drama

Stella Kon, author of Emily of Emerald Hill.

Stella Kon, author of Emily of Emerald Hill.

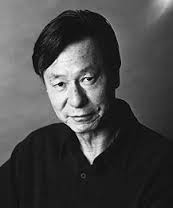

Kuo Pao Kun, author of The Coffin is Too Big for the Hole.

Kuo Pao Kun, author of The Coffin is Too Big for the Hole.

These two plays are monodramas, they were both staged in 1985, and they are widely considered as groundbreaking; however, they are quite dissimilar, as much as their authors are. Kuo Pao Kun has already been mentioned, since he was a leading figure of Chinese speaking theatre from the 1960s to the mid-1970s, before being imprisoned for almost 5 years. However, with The Coffin, he is about to dramatically change his theatre practice.

As for Stella Kon, she is a peculiar newcomer. She is a newcomer because Emily is her first play to be staged – but she had won the first two national playwriting competitions before, with a puzzling play (The Trial) about Singapore mixing local politics, Plato's theories and Socrates' trial, and another experimental play (The Bridge) set in a drug rehabilitation centre involving the staging of the story of Rama and Sita…

Different backgrounds, different ambitions, but almost simultaneously two English written monodramas that would eventually be considered as the first full-fledged truly Singaporean plays, by Singaporeans, about Singaporeans and for Singaporeans.

Margaret Chan, in Emily of Emerald Hill, 1985.

Margaret Chan, in Emily of Emerald Hill, 1985.

Ivan Heng, in Emily of Emerald Hill, 2011.

Ivan Heng, in Emily of Emerald Hill, 2011.

Emily of Emerald Hill tells the story of a Nonya, a Peranakan woman. Hence the character is definitely Singaporean, a descendant from this emblematic community we already mentioned.

Then Emily speaks English, but not British English even though her language is often quite sophisticated. As a matter of fact, her Singaporean English is as far from the Singlish localisms in Goh Poh Seng's later plays as from Lim Chor Pee's characters' English. Words and sentences from Malay, Mandarin or Tamil infuse the script, and grammar or structure often remind us of Singlish, this multiform and evasive pidgin that is definitely not British English but more a changing result from the Singaporean linguistic melting-pot. More importantly, even though Emily may remind us of actual Nonyas, Stella Kon crafted a stage voice for her, something that sounds familiar but is unquestionably theatrical.

Also, the play does not talk about Singapore, primarily because Emily just talks about her own life. Now, of course, her life is bound to Singapore History, so some scholars have argued that Emily is a metaphor of Singapore. They are wrong. The fact is we can feel the history of Singapore through the story of Emily's life, because she is a true Singaporean character; but Emily is not an abstraction, not a mean to state ideas about Singapore: she is the subject, the centre, the core of the play, which is precisely why we are led to feel so many things about Singapore rather than think about Singapore.

Last but not least, the play is not built like an English play. It is a monodrama, which is not such a common form in Western Drama (many monodramas have been staged recently, but Emily was created in 1985). Moreover, it definitely resorts to Asian dramaturgy. For instance, Emily may as well address the audience directly as withdraw behind the fourth wall, as in Chinese drama. Also, the character of Emily, a Peranakan matriarch, is the indisputable descendant of the famous wayang peranakan Nonyas (who, by the way, were often performed by men, as Ivan Heng did for the 2011 revival of Emily).

As a result, something that may be coined as an authentic Singlish dramaturgy finally hatched when Emily was performed. Surprisingly, another brand of Singlish dramaturgy, some kind of fraternal twin, crystallized almost simultaneously with the English performances of The Coffin is Too Big for the Hole.

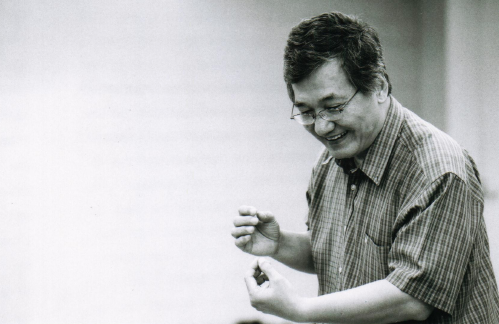

Lim Kay Tong, in The Coffin is Too Big for the Hole, 1985.

Lim Kay Tong, in The Coffin is Too Big for the Hole, 1985.

The Coffin is Too Big for the Hole, staged by Li Xie, 2010.

The Coffin is Too Big for the Hole, staged by Li Xie, 2010.

As a matter of fact, Kuo Pao Kun also uses an Asian theatrical style in his play, which he had practised when he was young: the xiangsheng (相声), a Chinese form of cross-talk or stand-up, a kind of story-telling directly addressed to the audience, far from Western drama tradition.

Then the story told by the character is plainly Singaporean. It takes place during a funeral service, and it elaborates on the fact that the coffin of the narrator's grand-father is too big for the standardized holes dug by civil servants. This contradiction between tradition and modernity, personal matters and political concerns, resonate in any modern society, but they are unquestionably grounded in Singapore where Chinese funerary practices collide with the scarcity of land.

As for the characters (the narrator, the funeral man and his boss), they might not be Peranakan, but their demeanour, their mindset and their interaction are totally Singaporean.

Finally, for the very first time, Kuo Pao Kun writes a play in English. To be fair, he wrote the script in Chinese, then translated it himself into English, with a few amendments that prove he had totally changed his set of mind: he was not addressing the Singapore Chinese residents about international issues anymore, but all Singaporean citizens about local issues.

It might seem paradoxical that Kuo Pao Kun would concomitantly resort to a traditional Chinese style while shifting to use English language, but I think that, on the contrary, they both follow from the same new vision Kuo Pao Kun developed from the 1980s until his death. Instead of defending any ideology through predetermined aesthetic forms, he would constantly try to stage his doubts, to question both his society and his art. Any language (including multilingualism as early as 1988), any drama style (multiculturalism would soon become central to his work) could then be used, modified, adapted, twisted, in order to chase the outlines of the elusive nation he was living in. In that sense, he had crafted a truly Singaporean theatrical set of mind that would inspire many future local artists, from stage directors like Ong Keng Sen to playwrights like Haresh Sharma.

1. Marc Goldberg, Le monologue à Singapour, naissance et développement d'une forme dramatique nationale (Monodrama in Singapore, birth and development of a national theatrical form), in CIRRAS, Françoise Quillet, La scène mondiale aujourd'hui – Des formes en mouvement, L'Harmattan Univers théâtral, February 2015.

“Emilie d'Emerald Hill” de Stella Kon – “Le Cercueil est trop grand pour la fosse” de Kuo Pao Kun: deux monologues singapouriens, translation and introduction by Marc Goldberg, Editions Les Cygnes, 2015.