◀ VISUAL ARTS ▶

EXCERPTS FROM RULES FOR

THE EXPRESSION OF ARCHITECTURAL DESIRES

DEBBIE DING

In this city, all primary school leavers sit for a special placement test known as the GEP (Geographic Education Programme) exam, which tests students on their geographical and cartographic understanding of the city. Students must be able to identify major arterial roads, discuss the history behind different place names, and suggest the most efficient transportation routes between different areas of the city. Like vehicles on a road, students are streamed according to their levels of understanding of the city’s geography and current roads.

The programme was first devised to encourage students with poor geographical knowledge to explore more of the city on their way home. Their test scores for this comprehensive exam directly affect their eligibility to apply for local secondary schools.

Depending on their test scores, if the student scores high on the exam, he or she will be eligible to apply for a secondary school closer to their registered home address.

Some foreign students studying in this city score very well on the exams despite not being born or spending their first few years in the city – their experiences of having travelled between different countries possibly having sparked an stronger interest in cities and their particular geographies.

Interestingly, local students who have scored the highest marks in their GEP exams often voluntarily choose to study at secondary schools which are very far away from their homes.

In this city, all private land parcels exceeding a certain minimum size must allocate at least 10% of their land to a "private garden camouflage zone". People who wish to use these private gardens for their own are permitted to do so only if they are in camouflage. Picnic mats and special picnic camouflage suits are manufactured and sold to suit every type of gardens.

Picnic goers blend seamlessly into the private gardens, private landowners are unable to see the picnic goers in their parks – making them invisible whilst still actually completely visible.

Some entrepreneurial individuals trawl through the streets for plant material, sewing leaves, grasses and twigs into suits. In particular, homeless people have been taking advantage of this scheme, devising the most ingenious ways of producing a camouflage suit for almost no cost, and becoming virtually invisible within some of these parks. Many of the homeless people seem to have mastered the fine art of blending in and remaining unseen whilst still in plain view.

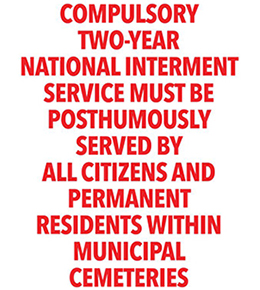

In this city, all of its deceased residents are required to be interred in the grounds of the city’s municipal cemetery for a period of 2 years after their deaths.

A special islet near to the city was designated as a dedicated cemetery zone, where the dead would serve out their minimum two years of internment service.

The internment conscription policy was first devised as a method of evoking a stronger sense of geographical attachment, as the family of the deceased would be obliged to visit their dead at the city cemetery during the 2 years of internment service.

After serving out a 2 year internment service, the family of the deceased resident is then served a notice informing them that they are now allowed to move the remains of their loved ones to any other private burial plots, or to any other columbarium.

Despite many families having objections to the heavy-handed policy at a very emotional time of their lives, in the end many voluntarily choose to leave their dead in the municipal cemeteries. Over time, with the constant flow of visitors visiting the island to remember their dead, the city cemetery becomes alive with the celebration of memories – an archive of all the stories and lives of the city’s residents.

RULES FOR THE EXPRESSION OF ARCHITECTURAL DESIRES

Debbie Ding, Rules for the Expression of Architectural Desires (excerpts), 2015The time is neither future nor past. The place is neither East nor West. The design of our built environments begin with ideas, and these ideas are articulated in ways which may be conceptual, fuzzy, or imprecise.

What we find is that the material of a city is immaterial at its very core. Our attempts to define rules for society precede every action, motion or change in our urban environment, and our urban experiences can be altered when we change the manner in which we define a city.

Debbie Ding presents a selection of speculative rules, schemes, devices and instruments for the urban and social design of a city.